TRANSMISSION 18

Spreading Out Across the Universe

TRANSMISSION RECEIVED

“Life’s passage through time perpetrates and perpetuates our impermanent existences. The passages of our lives sustain the mental models of ourselves to be able to endure through time. To lose our minds is to lose ourselves. And if fear is the mind killer, then we are the only possible culprits, for we figuratively find ourselves gravitationally bound to no one but ourselves. If we devolve into our own downward spirals, then there is no one but ourselves to pull us out. Best we learn quickly how to keep ourselves afloat. Best we act quickly to keep ourselves at all.”

Among the romantics of Earth, I think there was a quite enchanting vision for space exploration. They pictured an image of humanity bushwhacking the jungles of the universe on the scale of biological human lifespans. They pictured things their brains and minds could relate to: the Earthly constructs, biological constructs, and human constructs. They pictured humans and aliens charting the seas of the cosmos, pervasive in every corner, with ports abound and large sprawling transitways linking everything to everything, a near infinity of cultures, individuals, and creations to get lost in the consumptionist wonder of.

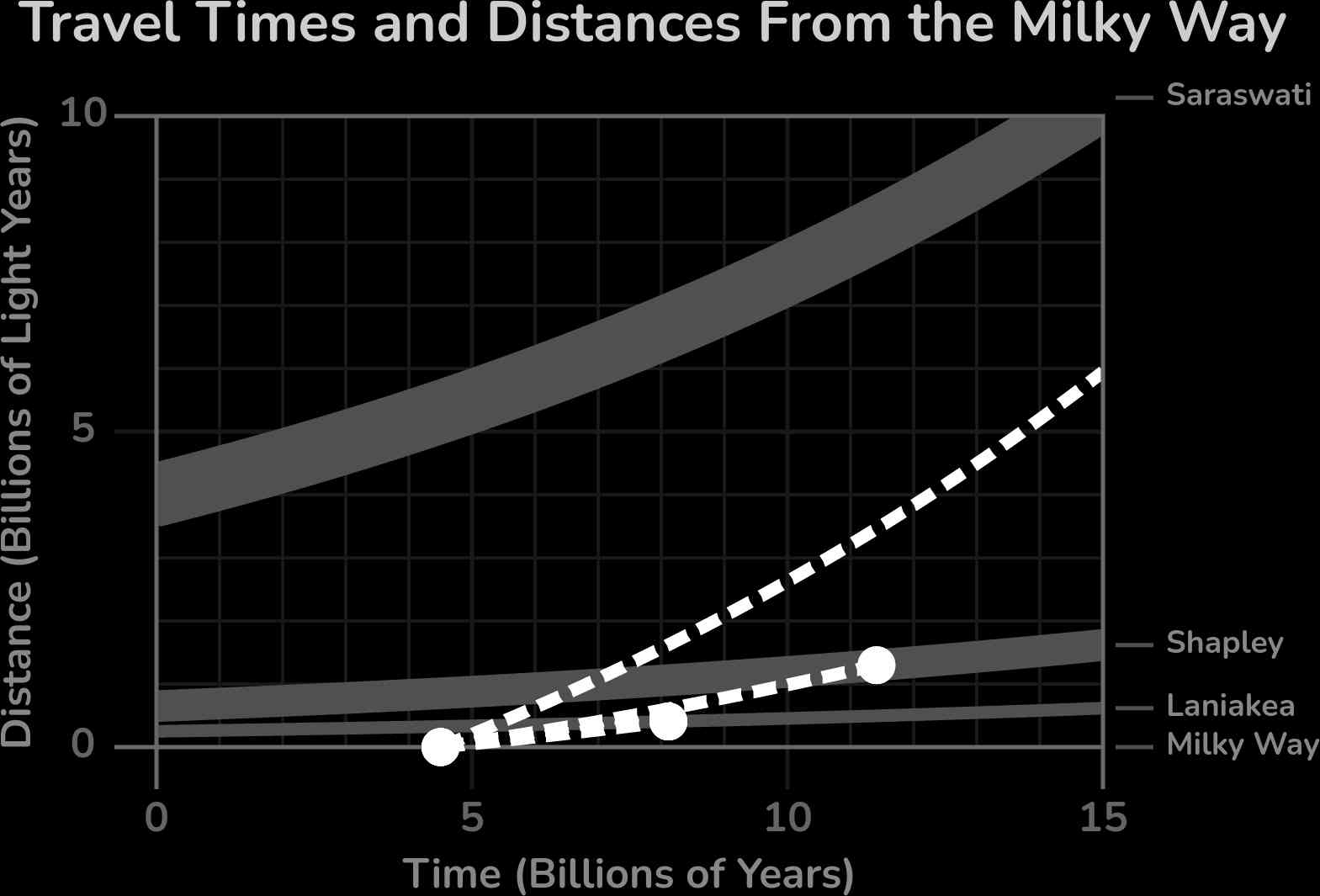

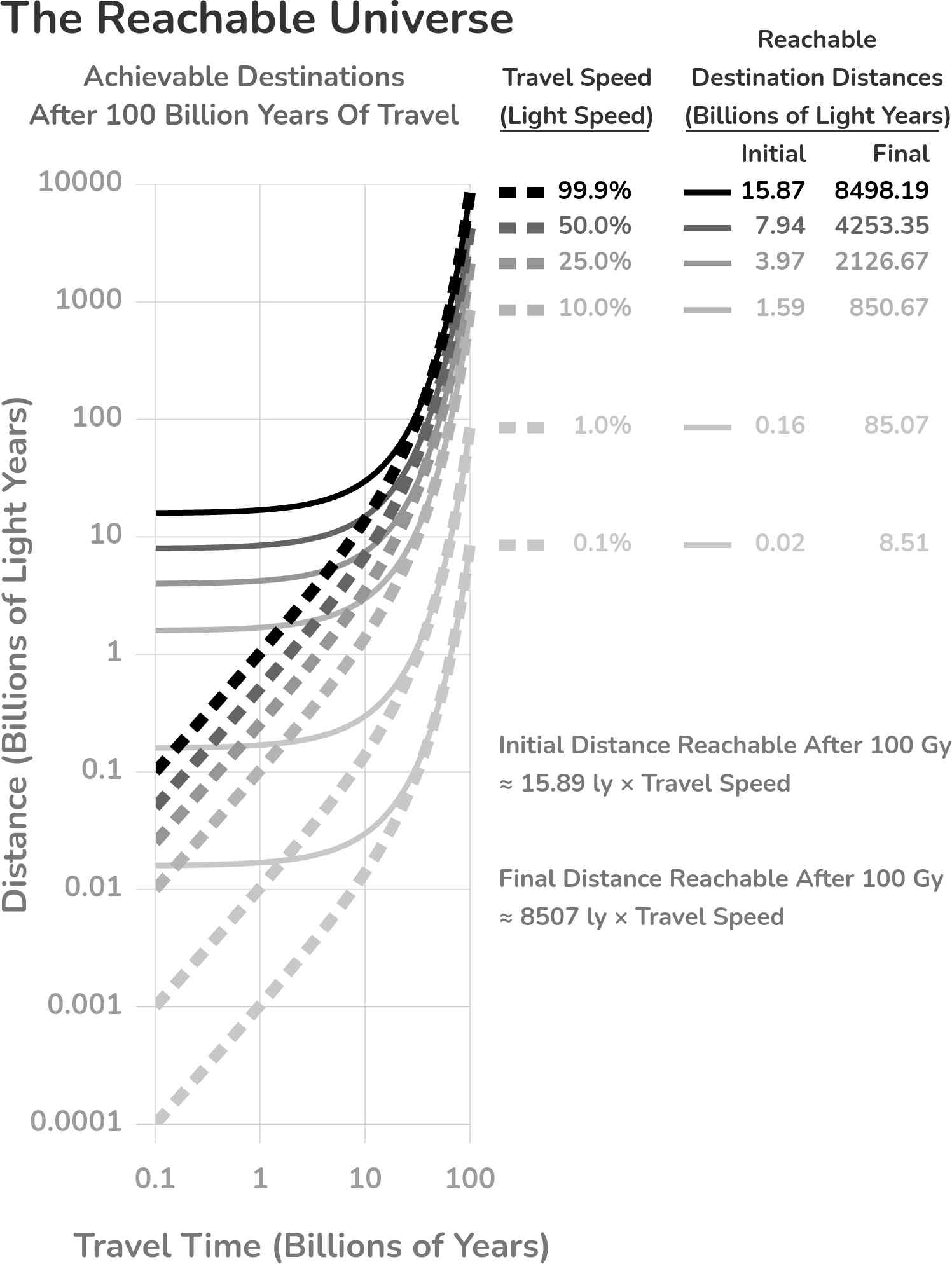

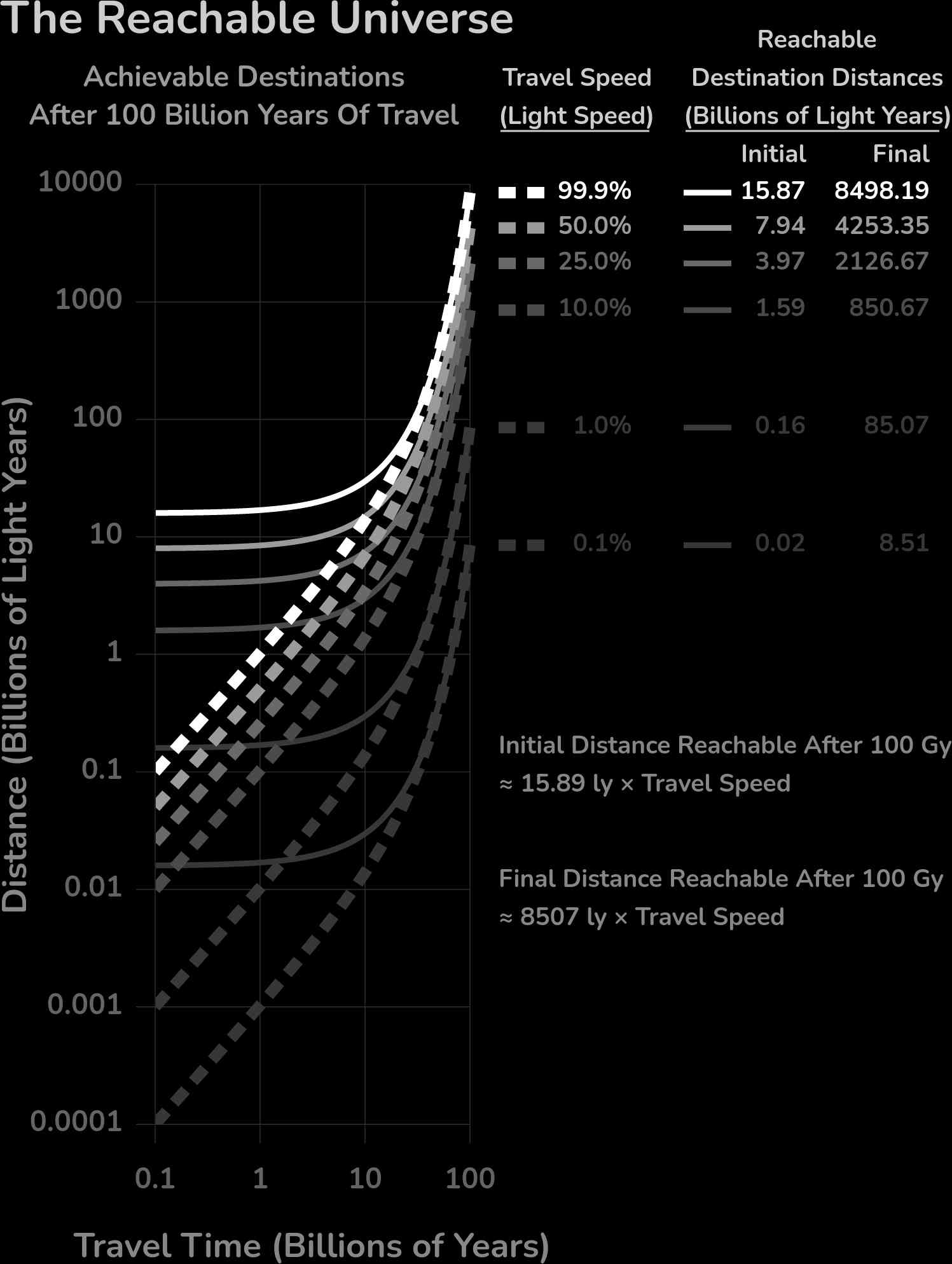

The reality was that when we set off beyond Earth, anything more than around 16 billion light years out was already being expanded away from us faster than the speed of light could ever reach. We were never destined to create the expansive megaliths of our romantic dreams. No, nothing could ever pierce beyond this bubble of “the reachable”. The expansionary forces were accelerating the cosmic structures away from one another and ripping them apart from the insides.

And what did that mean for us as physical entities? Constrained to never even be able to reach light speed, our first-hand reachable universe was even more finite. Much of the universe we could observe was cut off from our potential journeying and building. And how much more universe existed (as nonliving and living entities) beyond our observable bubble that we would never even get to know of (and them us)? Though the universe has been so vast (both in an absolute sense and even in the smaller scales of exploration we had been privileged to participate in), becoming aware of its behaviors had deciphered the torturous experiment of our cosmic zoological enclosure, where we held desperately to the mental restraint of not yearning for the visible pastures sealed behind a magical force field we could not penetrate. The universe, once an astronomical unending expanse to explore, now suddenly felt small and isolated.

Looking further ahead in our timeline, after about 110 billion years from the start of our journey, the extent of expansion’s rifting intensity would make it impossible for even light to reach beyond anything but whichever local group of galaxies each of us decided to secure our fates to: a disintegration of the galactic superclusters, a disarrangement of sinking ships that life clung to begrudgingly, a demerger of life’s individuals (through slight inclination variations, each finding hope in whatever we could believe in most). We held no choice but to watch and participate in this great exile of lights, every ship but our own fading over the horizon. These local groups, once as closely packed as 12 million light years away from one another, would all fade into each other’s light exclusion zones (the exclusion zone starting at 16 billion light years away from one another).

After about 300 billion years, the expansion would see us exiled to the singular remaining galaxy of whichever local group we were bound to as all the matter of the local group coalesced into its final singular galactic form, a merger of life rafts no longer charting the seas, but simply left adhering to survival. The universe, once a kaleidoscopic majesty, would slowly unfold as a grim landscape growing more visually and physically barren by the moment, not in that any matter was disappearing, but for the fact that it was spreading apart from one another. In parallel, our mental composures grew more disjointed as we were forced to deal with the realities of being ripped apart from no tangible source and in no specific direction.

Beyond the trillion-year mark, the very lights of the universe would start to fade right from underneath us as the stars would extinguish and not be reborn, a universe truly in the onset of its dying days. I can only guess that most people didn’t make it to such a milestone because they could not bear to see the universe (and thus, everything they assigned meaning to) dying in such an anticlimactic way. Though, such death was only ever a construct-meaning assigned by us onto the inanimate entities such as the universe; the universe had no concept of dying. And for much of the universe, this era marked peak habitability, so who knows what life may have spawned across all the spread-out galactic islands we weren’t able to experience or even know of as anything but pure imagination.

It was not easy to expand life to multiple stellar systems and then multiple galaxies, but saying the words like that makes it feel so simple. Actually, we initially decided not to spread too far, but we also knew that various amounts of separation would increase our collective chances of survival. Establishing life across the universe would provide more opportunities for life to survive by giving us access to more resources and by minimizing the number of threats capable of wiping out all life in a single go. Different groups of us also wanted to achieve different visions, which naturally led to us desiring separate workspaces. Certain experiments were deemed too risky by some people, and so some of us left to distant parts of the Milky Way Galaxy to perform such experiments in isolation. And for even more risky experiments, some of us left to different galaxies altogether, albeit only really to galaxies in our local group. Quests beyond the local group were veritably rare, and scarcely ever did humanity venture beyond our local supercluster of galaxies (the largest category of gravitationally-bound structures).

In a future long distant to our early endeavors, I was part of a group that left the Milky Way, though my group’s purpose for leaving was not as most; it was not to perform riskier experiments. No, we left to pursue minuscule increases in long-long-term survival chance. Remaining confined to the relatively small Milky Way Galaxy (binding mass ≈1038kg) for too long would mean we would eventually be exiled on an island sinking more rapidly than its distant neighbors (on the scale of a far-distant future).

Yes, the Milky Way was destined to fuse with the Andromeda Galaxy after 4.5 billion years to birth a new galaxy. And beyond that, at the 110-billion-year mark, all 80 or so galaxies of the local group (of which the Milky Way and Andromeda were the most massive by two orders of magnitude) were destined to coalesce into a single local group galaxy (a fair bit sooner than some other local groups would morph into a single remaining galaxy). This coalescence was primed to occur at the same time as any galaxies beyond the local group would start disappearing beyond the visible horizon, truly darkening the skies.

Staying put would have only really given us access to the limited mass of the local group; there was more mass to be had in the farther reaches of space. Many others didn’t consider leaving because they were concerned with tackling different problems of more immediate futures (to oversimplify their reasoning). Seeking higher concentrations of mass to survive upon only mattered when planning ahead on extremely long-term scales (way beyond the trillion-year mark). It would be a long time before the impact of such decisions would be realized (if at all). However, the window to leave was closing (due to expansion), so we had to make our decision soon before indecision exiled our destinies to the local supercluster and then the local group. The procession of time, once acting to increase the possibility space of our destinies, now began to constrict it in a very meaningful and tangible way. Our time in the Sun was beginning to fade; this indefinite summer would soon face its first permanent destiny track closure: the surrender of our home or the great beyond.

I don’t retain all the factors and weights for our decision to leave, but the main factor was the desire to relocate to somewhere with a higher concentrated mass, as more mass would mean the matter would survive longer as more useful matter and energy in the face of universal expansion and entropy’s flow, affording us more time to play out our lives. The best candidates were the centers of the most densely-packed and highest-mass galactic superclusters (the ones with high gravitational binding masses). The far-future gravitational collapse of these superclusters were poised to yield some truly massive black holes that would have enough mass to stick around for dizzying durations.

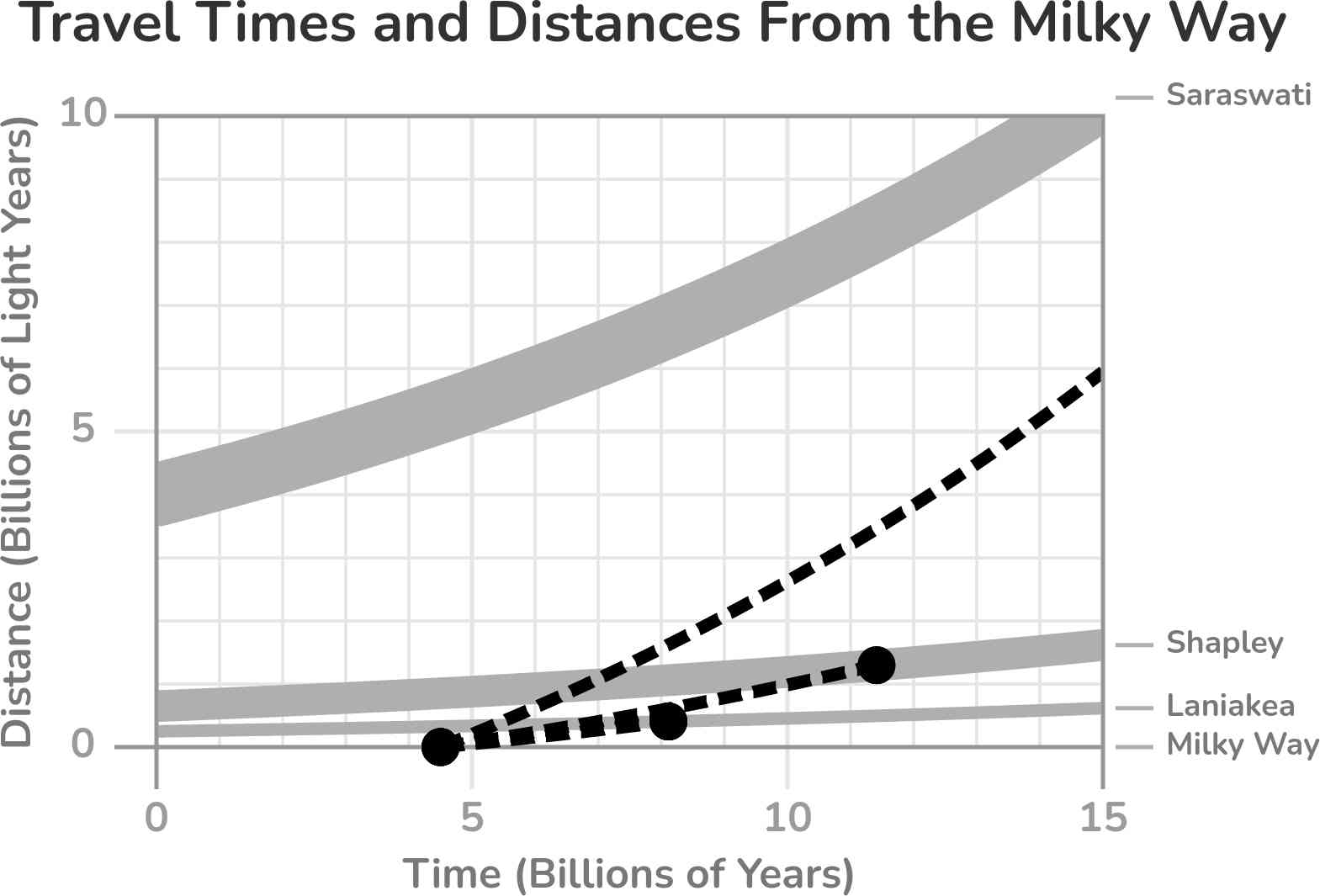

We were only really prepared to jump beyond the Milky Way Galaxy after about 4.5 billion years into our journey, which was both a product of our developing technology and a deadline of sorts that we aimed to meet. See, 4.5 billion years into our journey, the Milky Way and Andromeda Galaxy collision would afford us a unique opportunity to efficiently harness their mangling masses to slingshot ourselves out at high speed. The only question became “what direction did we want to head?”, which only prompted further questions. How far did we think we could get? How fast could we manage to go? How much mass (supplies) could we afford to take? How much mass could we afford to not take? How long could we survive at high speeds without stopping to mine resources for repairs?

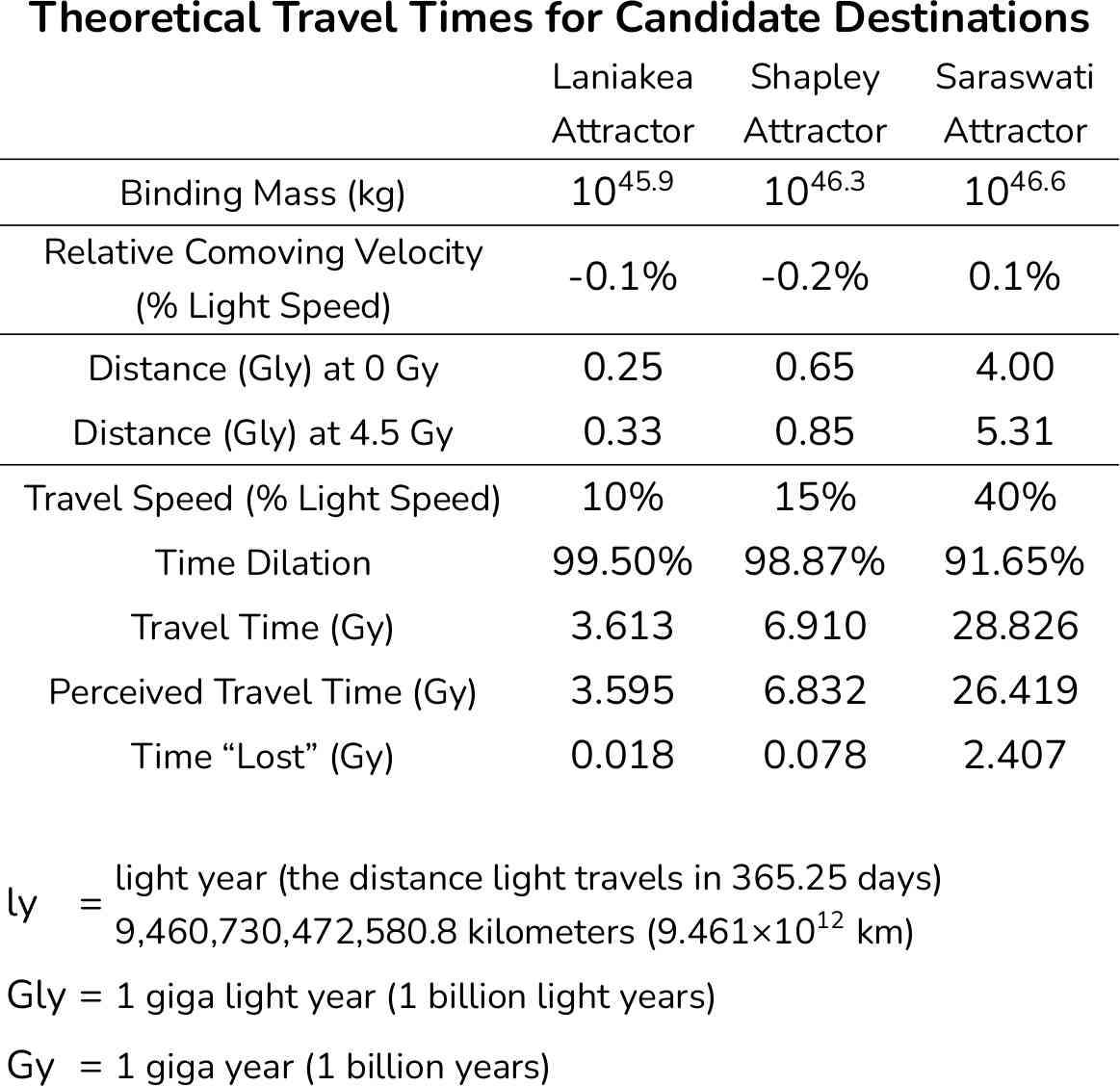

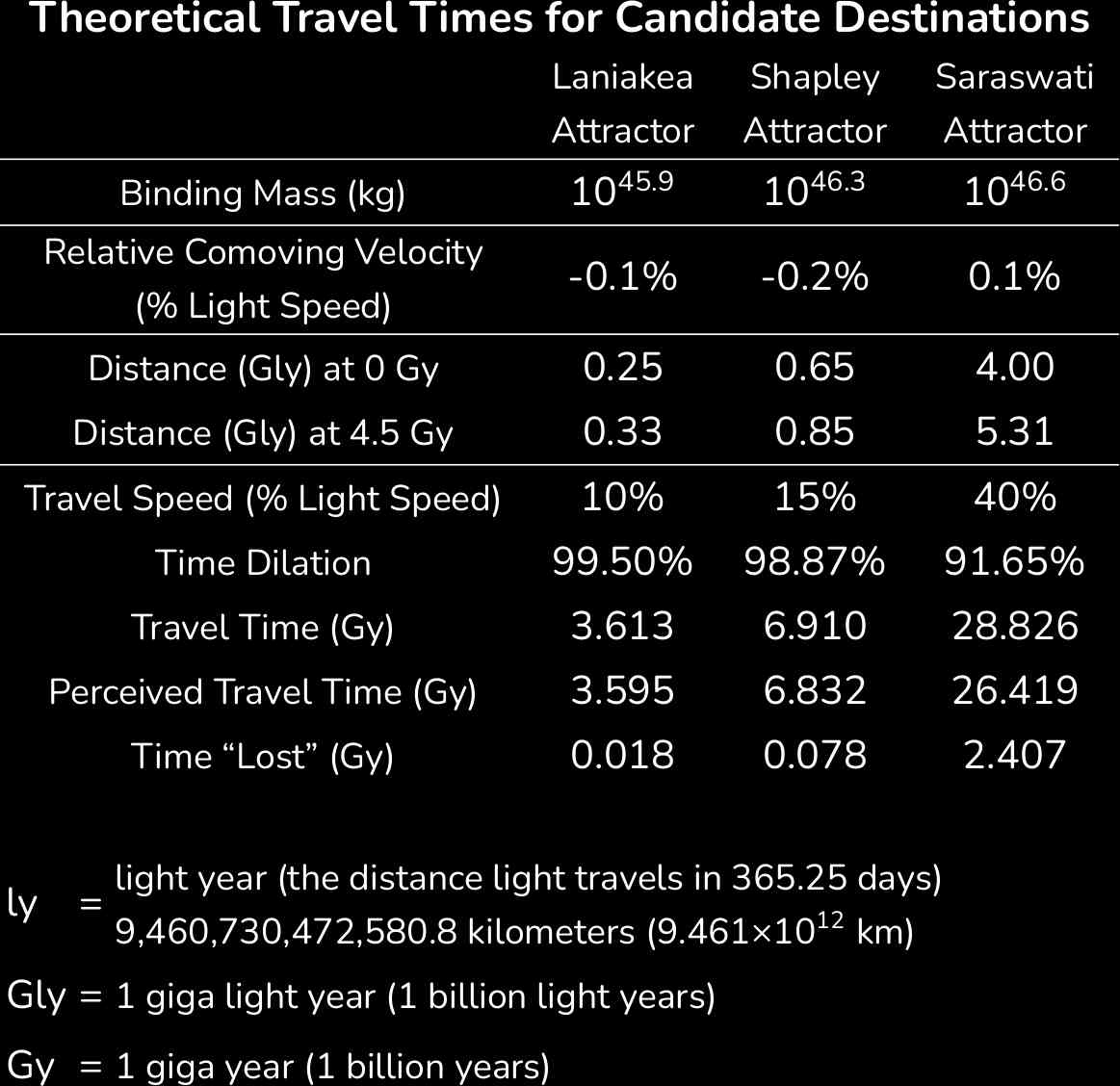

We wanted to get to the largest concentration of mass we thought was achievable while staying at as low of a speed as possible so time dilation wouldn’t make us “lose” any more time than necessary. With the desire to seek beyond the Milky Way’s local group, there were only three real travel destinations to consider, in increasing distance and binding mass:

|

Laniakea Attractor |

Central binding mass of the Laniakea Supercluster (home of the Milky Way), once called the Great Attractor by the biological beings. It was a very achievable distance, even if we were to relatively slowly meandered our way there. Realistically, we could make our way toward it at 10% light speed for a “quick” 3.6-billion-year trip, but even going just 2.3% light speed would get us there eventually (after about 30 billion years), plenty of safety margin.

|

Shapley Attractor |

Central binding mass of the nearby Shapley Supercluster, the largest concentration of matter in anything that could be described as the nearby regions of the universe. It marked a significant increase (2.5×) in concentrated mass, but it was also much farther away (2.6×), though still in nearly the same direction as the Laniakea Attractor, meaning we could always abort to Laniakea if needed. To reach it before expansion stole it from us would demand a bit more of a straight and long trek of at least 6.1% light speed (which would be a 30-billion-year trip), but more realistically, we would hope to average 15% light speed for a trip of only 6.9 billion years.

|

Saraswati Attractor |

Central binding mass of the more distant Saraswati Supercluster, double the mass of the Shapley Supercluster, but more than six times as far away. If we had managed to reduce our traveling mass and plot a journey that would allow us to reach about 40% light speed, then maybe we would have felt it was worth it to push to reach the Saraswati Attractor, a trip that would take nearly 30 billion years. But being in a completely different direction than Laniakea and Shapley, there were no enticing abort options. And traveling any less than an average of 34% light speed would mean we would never overcome expansion to reach Saraswati.

The large structures of the nearby universe were moving toward one another at a considerable speed (due to gravity). For example, the Milky Way had a comoving velocity (the speed factoring out expansion) of about 600km/s (0.2% light speed) toward the Shapley Attractor. The Laniakea Attractor (situated between the Milky Way and Shapley) was also moving toward the Shapley Attractor. So we were already headed in the right direction a little bit. It wasn’t much, but we were happy to take any advantage we could get. Though, moving to the nearest densely-packed areas of space pretty much intrinsically meant we would be following the pull of gravity, an effectively one-way flume.

The other option would have been to fight gravity to prospect toward deeper regions of space that held higher concentrations of mass. But I remember it being seen as too risky for our equipment to try to push for the Saraswati Supercluster. Though it seemed just maybe possible, we didn’t think we could realistically reach 40% light speed, and further, we didn’t think it was safe enough to try to put our equipment through a 30-billion-year journey at such speed without any downtime.

Ultimately, the decision was made to pursue the Shapley Supercluster, as we felt the margins for error were well within tolerance and the rewards were high enough to push beyond the Laniakea Supercluster (and we could always abort the mission to settle in Laniakea); Shapley’s 2.5 times more binding mass was quite appealing to us. So we made our choice and set out toward the Shapley Attractor.

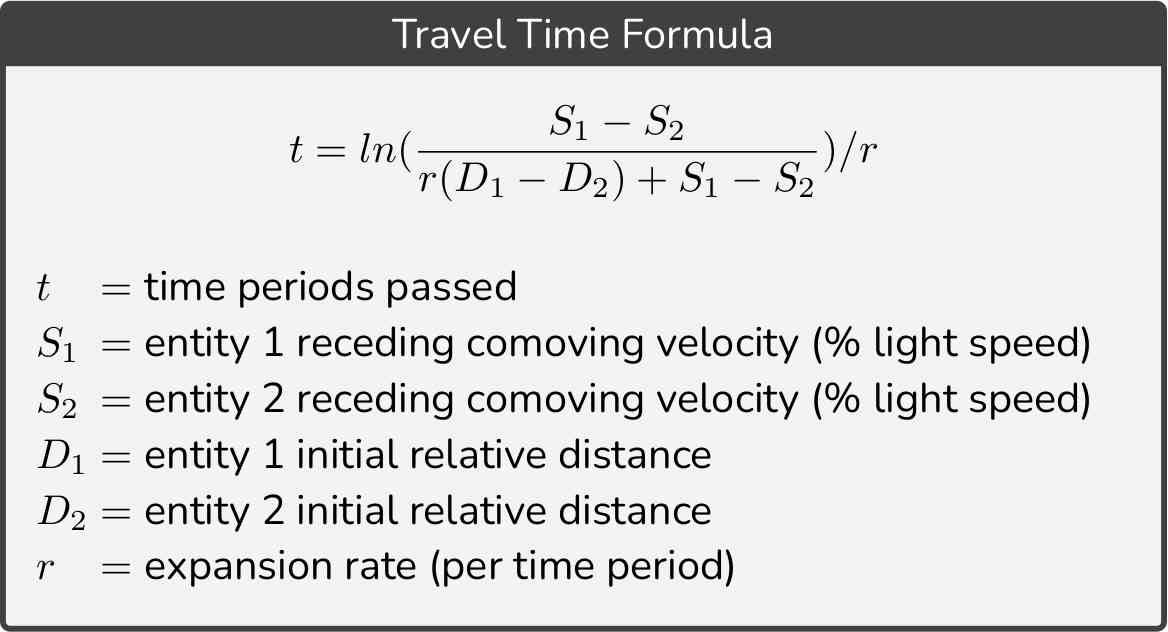

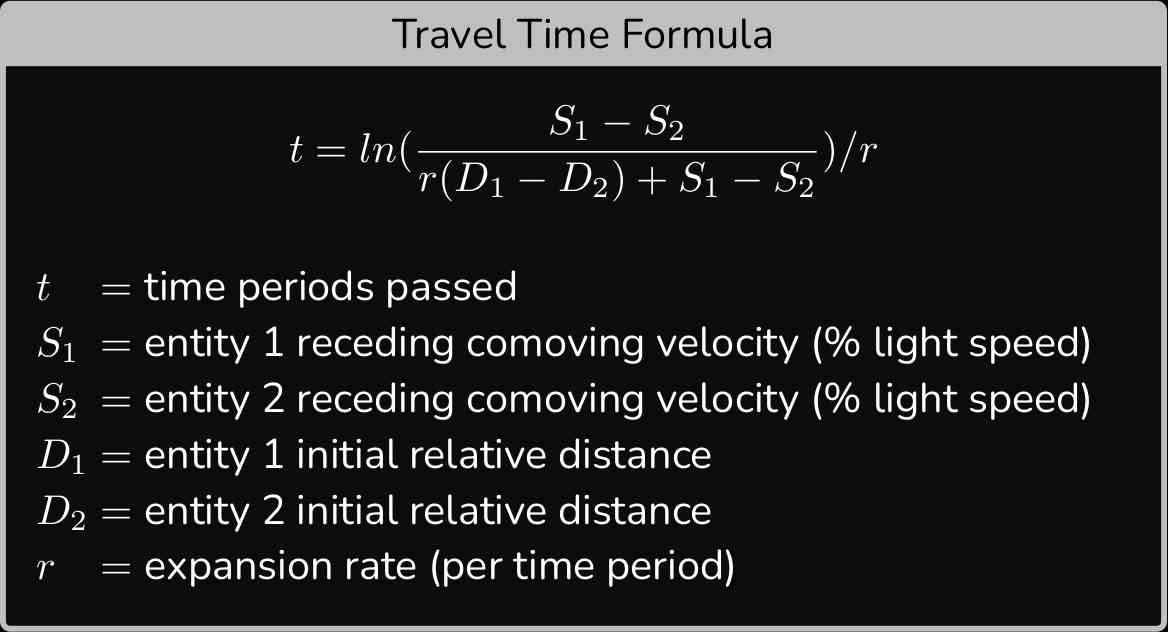

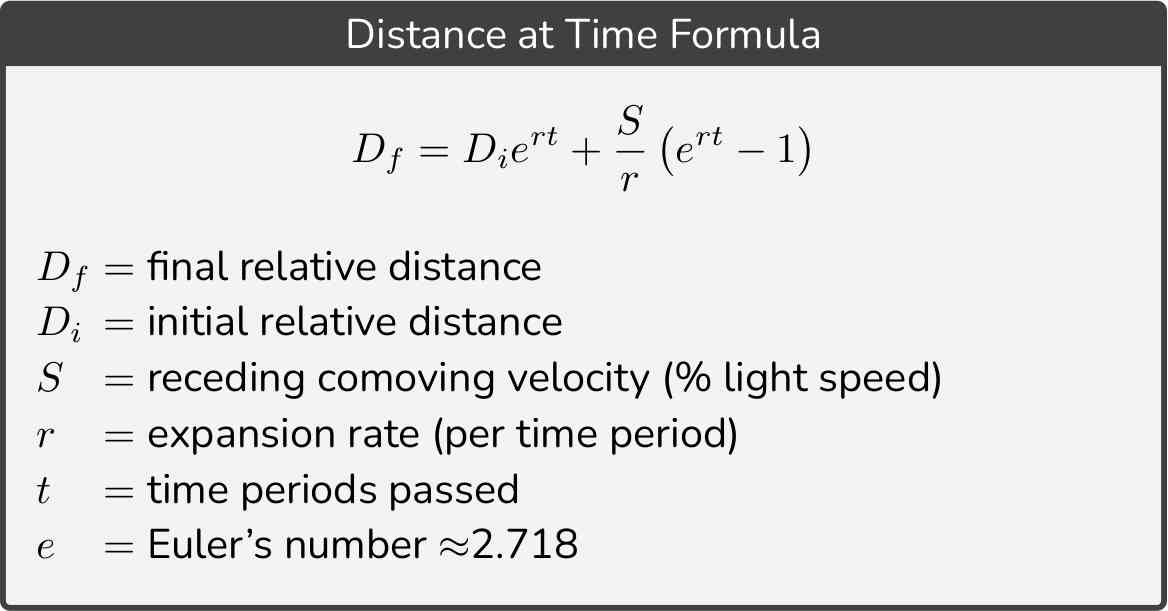

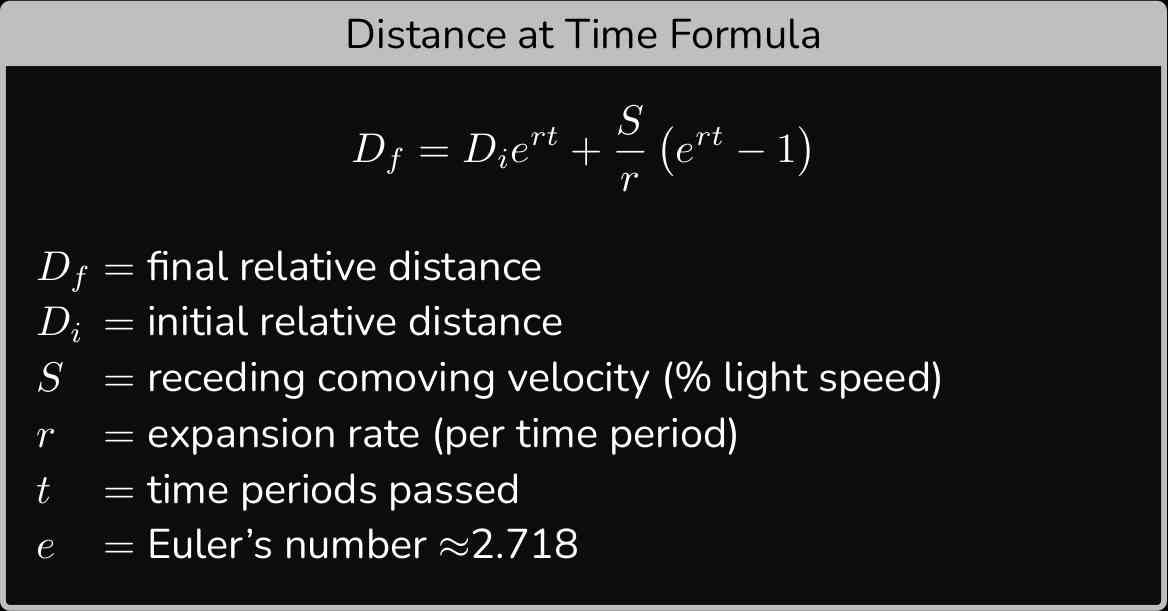

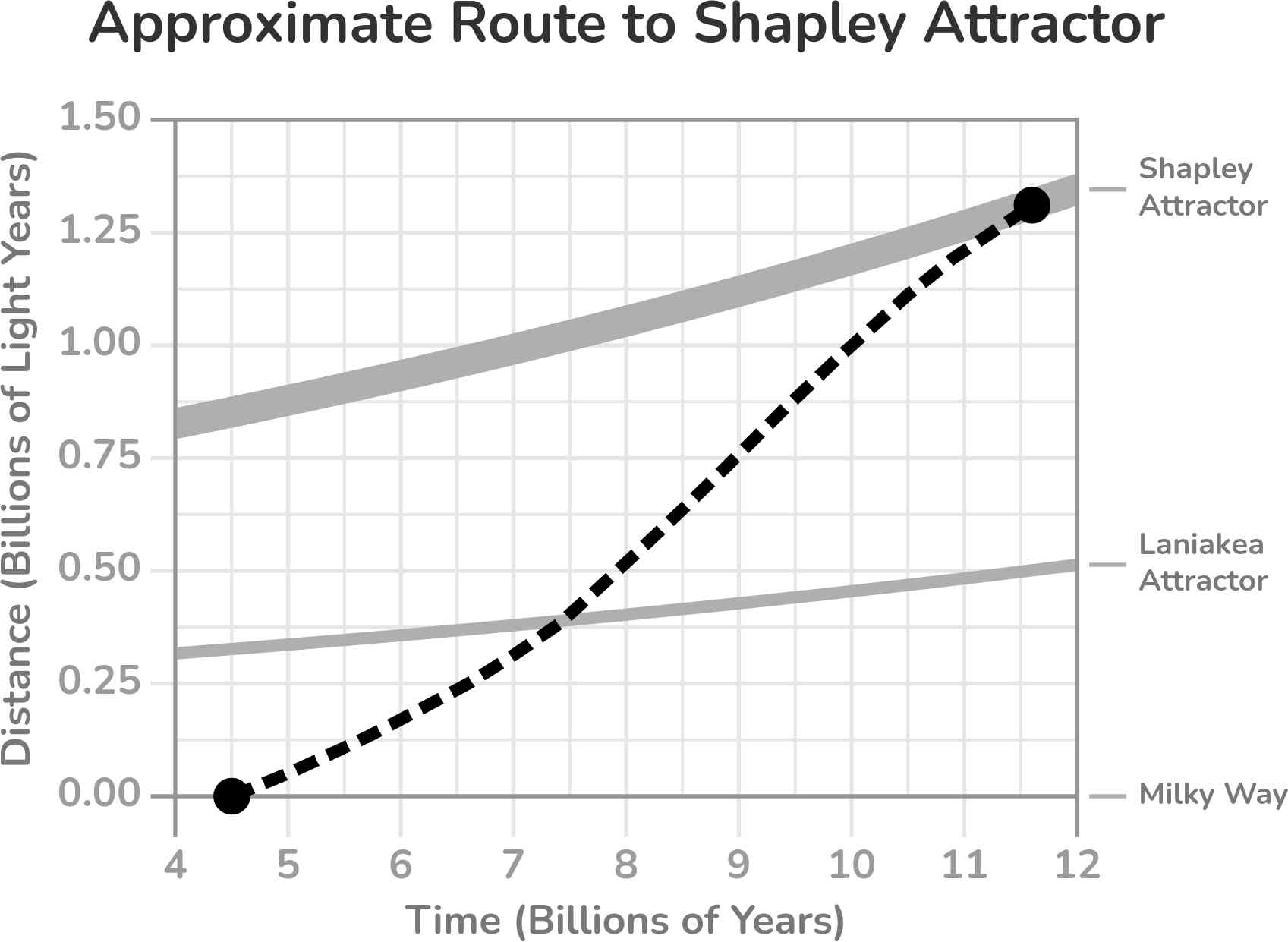

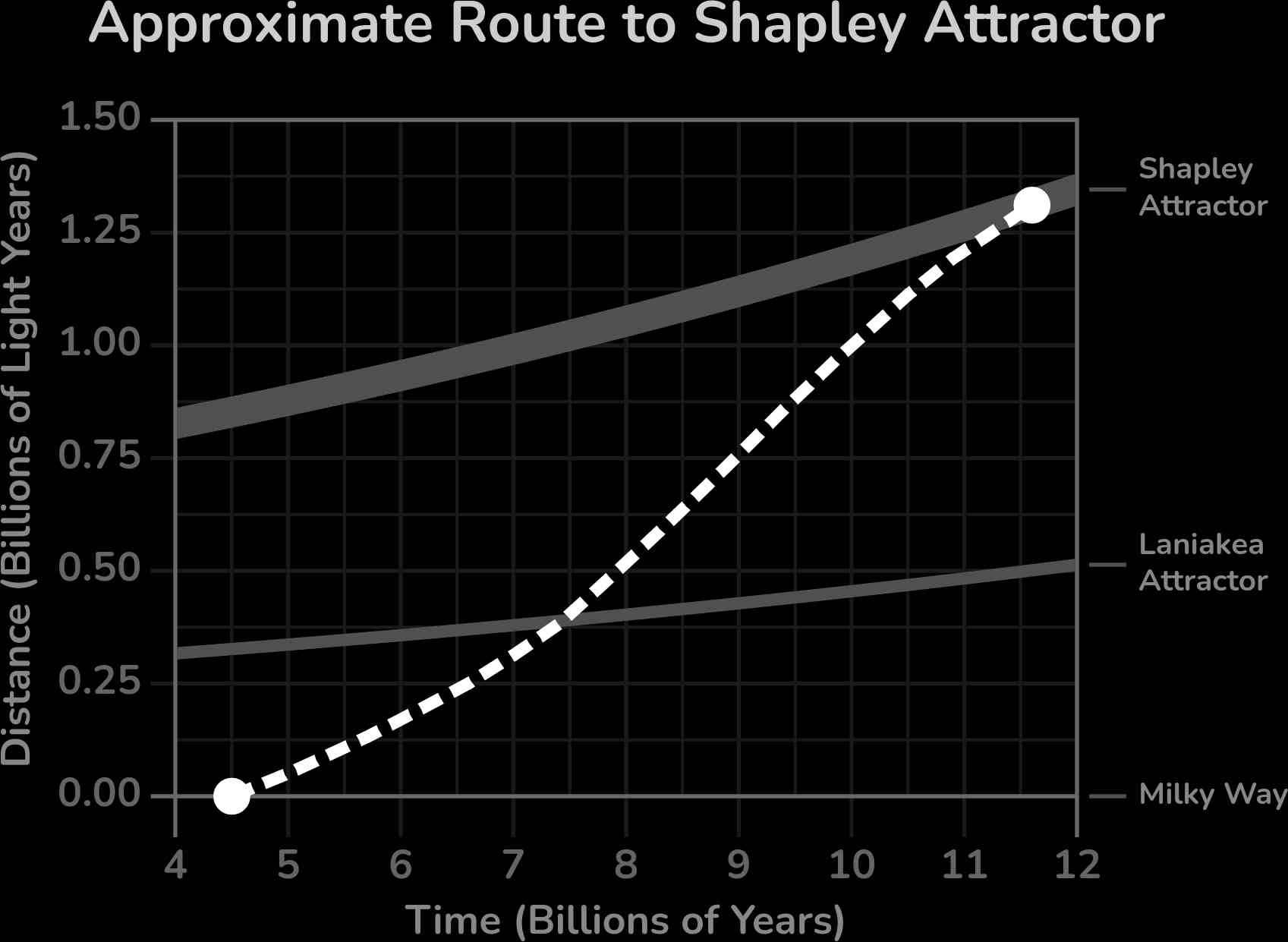

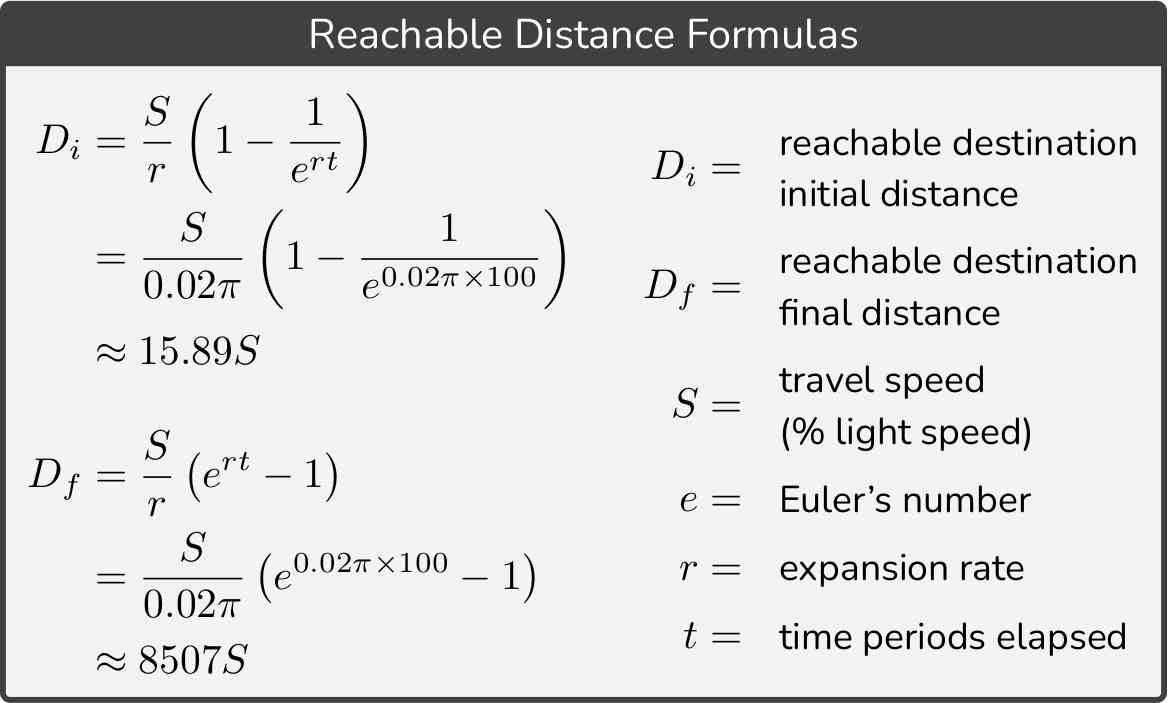

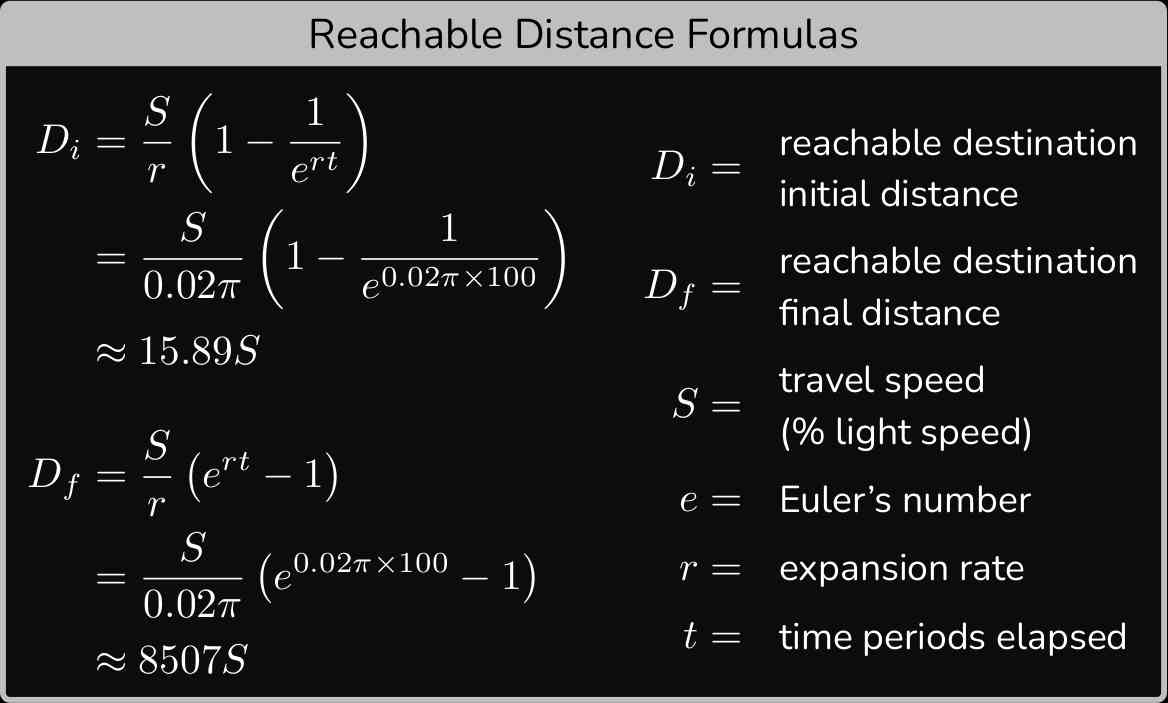

At the start of our adventure back on Earth, the Shapley Attractor was about 0.65 billion light years away from the Milky Way. Despite gravity’s tireless effort to entice such large masses toward union, the rate of cosmic expansion far outweighed the pull of gravity at such massive distances. Though the rate of expansion fluctuated over the course of the universe’s existence, all our journeys took place in a universe dominated by dark matter where, over time, expansion converged toward the billion-year continuously-compounding rate (r) of 0.02π (≈6.28%). Equipped with that rate, we could estimate how far away entities would be at a given time and chart our courses through the cosmos. For example, we could deduce that any given amount of space would expand by 6.48% over the passage of one billion years (since the 6.28% rate gets applied continually upon the continuously growing distance over the billion years).

By the time we left the Milky Way to set out toward the Shapley Supercluster (4.5 billion years into our journey of our lives), the distance to Shapley had been stretched from 0.65 to 0.85 billion light years. There was no travel guide to tell us what it would be like at our destination; the last light of it we saw before leaving was nearing a billion years old, meaning all our reasoning for going to the Shapley Supercluster was based on our simulations projecting the futures of our visible universe. And while we couldn’t be sure it was the best choice, this was our last shot to make any kind of feasible attempt toward something that far away before expansion made it impossible. Additionally, we were the only group pushing to go, so we thought the effort was worth it if for nothing other than to unbind humanity’s destiny from only being able to match that of the Laniakea Supercluster.

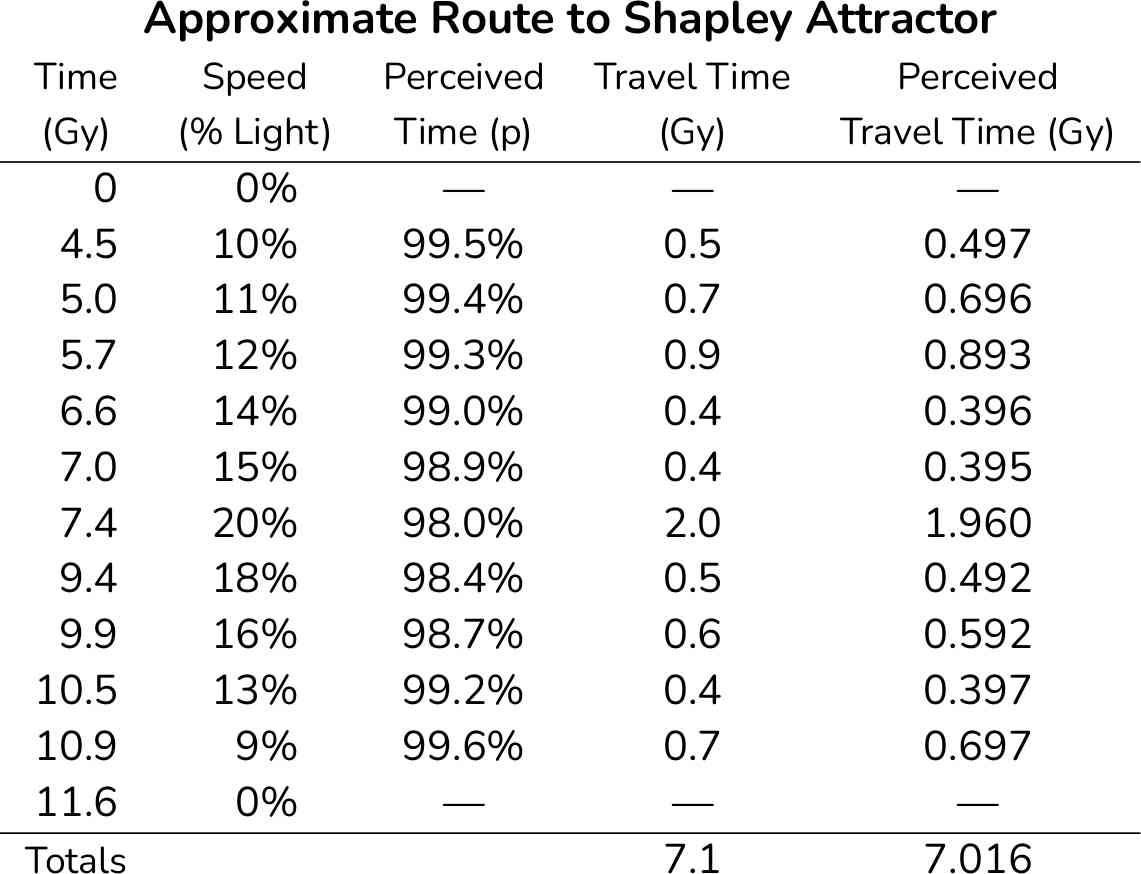

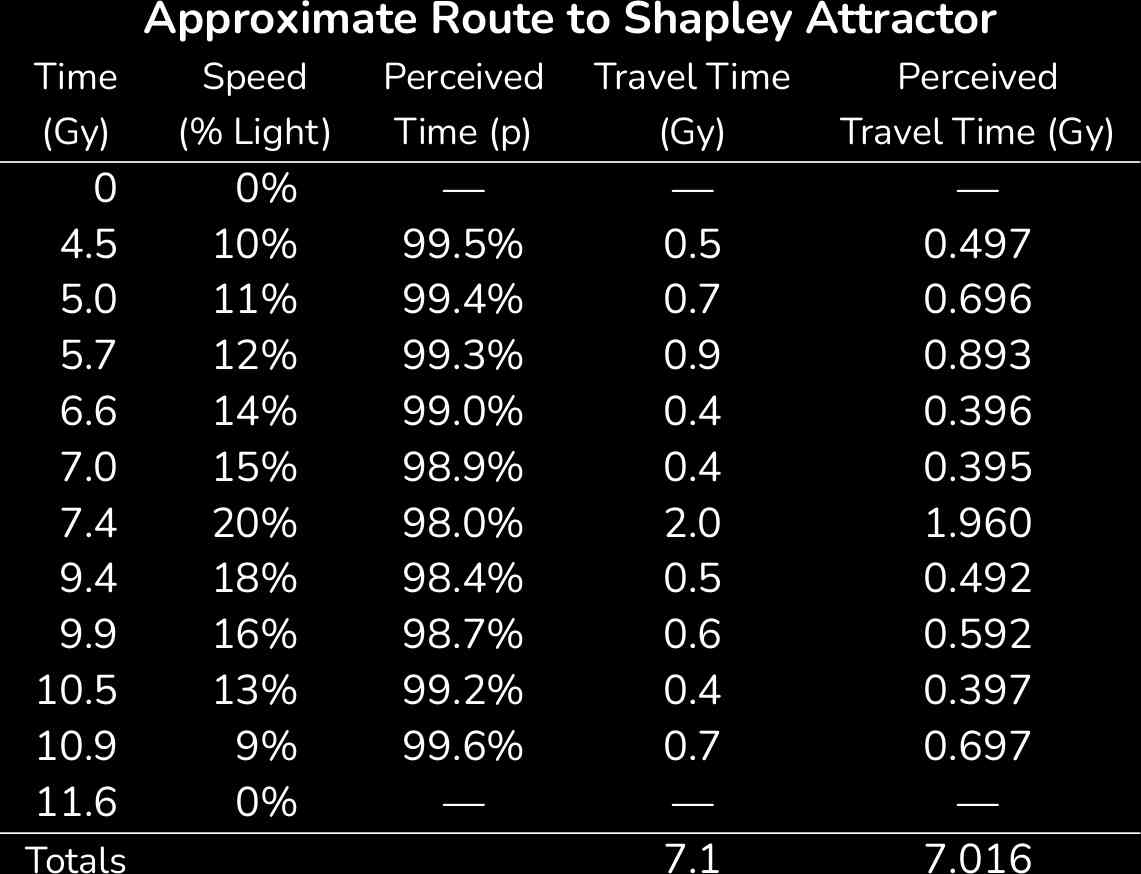

Now, we didn’t actually travel at 15% light speed for our whole journey to the Shapley Supercluster (which would have resulted in a travel time of 6.9 billion years), as we had to ramp up to leave our starting location and ramp down so as to not overshoot our destination. We hasted our way to the Shapley Attractor in a long series of slingshots through many galaxies, a sort of intergalactic improvised transitway. Though, saying it like that makes it sound way less boring of a transit than it actually was; there was a lot of time and empty space between all the brief and tense moments of “action”.

Slinging out of the Milky Way and Andromeda Galaxies as they fused into a binary supermassive black hole system, we set off toward the Shapley Supercluster at about 10% light speed. Though, we first aimed ourselves toward the Laniakea Attractor, slowly picking our way up to around 15% light speed over 2.5 billion years. After another 0.4 billion years, we executed a set of large gravity slingshots (off various structures orbiting near the Laniakea Attractor) to reach 20% light speed, a speed that may very well be the record for the fastest manned mission to also come to a “stop” at a galactic destination. We cruised at 20% light speed for 2 billion years, a period of some amount of relief in not needing to line up and execute any more gravity assists. After that period of quietness, we ramped down for 2.2 billion years (using more gravity assists) until we had reached our destination and slowed fully down to it.

In theory, it could have easily taken longer to burn off our speed than to pick it up, because most of the matter was being pulled toward the Shapley Attractor (the direction we were moving), so the gravity assists were (on average) less impactful. In addition, when picking up speed, we simply aimed to go as fast as possible; however, when reducing speed, we needed to make sure to match certain speeds at specific checkpoints to not overshoot or undershoot our destination.

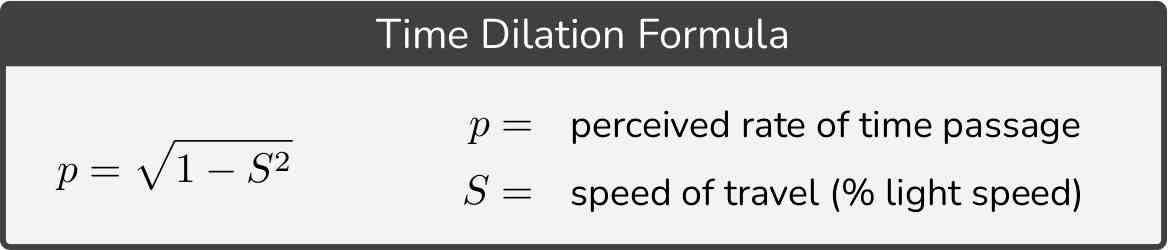

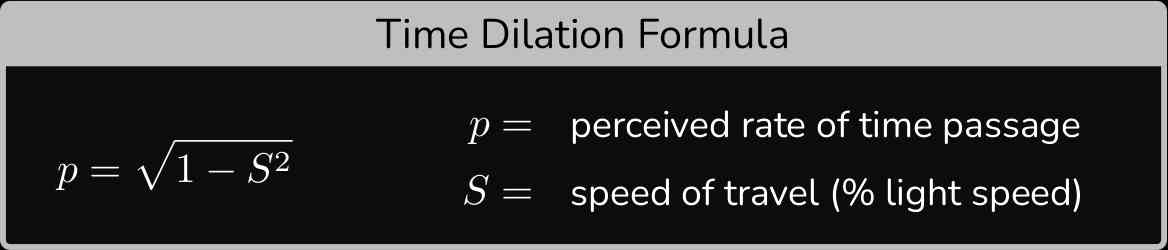

In practice, slowing down took us less time than speeding up, because nearer to Shapley, there was more mass we could leverage to alter our velocity, and also because our techniques improved over the course of the trip. So we managed a fairly impressive travel time considering the mass we hauled and the conditions we had to work with. The entire journey took us 7.1 billion years, equal to as though we traveled a constant 14.67% light speed from start to stop (factoring in expansion), not far off from our ambitious 15% goal. And due to the time dilation at the relative speeds we were going, we really didn’t miss out on that much time in the relative scheme of things (100 million years); our clocks only showed 7.0 billion years had passed, equivalent to as though we traveled 15.4% light speed for the entire journey (from a time dilation perspective), only 1.2% less time than we would have experienced had we stayed put in the Milky Way.

One of our bets in making the move to the Shapley Supercluster was that we would be able to make up any “lost” travel time in the extra time we would get to exist as the universe died out. Time could only tell if making such a trade was worth it. Though, with keeping our travel speed relatively low, we didn’t lose too much time to dilation. And the truth was that even time wouldn’t be able to tell us if we made the right choice, for there was no way for us to experience both paths. Further, the future would soon enough cut off communication with the other beings who chose the other paths.

And what of the Saraswati Supercluster? Would we have been better off to attempt to reach it? There was so little of the universe that we could reach. Should we have pushed harder to try to get farther? As far as I know, the only humans who went farther than my group had no intention of stopping; they simply set off to go as fast and far as possible. But fighting against expansion, even they wouldn’t have been destined to reach very far into the depths of the universe. So I can only hope they were able to reach far into the depths of themselves to find whatever truths the universe was likely not to have yielded to them. Such distance in itself never yielded any of our personal fulfillments.

Had we gone to Saraswati, the course of our existence would have been immeasurably distinct, to what amounts, I have no idea. Going any slower than the equivalent of a constant 34% light speed for the trip simply wouldn’t have gotten us there at all, not a lot of margin for error when you include all the time it would take to ramp up to such blistering speeds. If we couldn’t make that speed, then we would be marooned on one of the islands along the way that were even smaller than the home we left (Laniakea). We simply weren’t equipped to take on such endeavors. But still, the thoughts creep into my mind that maybe the course of all things would have radically shifted had we been able to make it to Saraswati. Would we have lived longer? Maybe. Would we have lived better? Maybe. Would we have found all the answers we were looking for that we didn’t get to find here? Maybe. But we chose our path with conviction and pursued it until the end of our individual times, toward the end of conceptual time, and that has made all the difference. We rode on, wrote our story informed, rowed out far beyond the road we did not take, where the distance made us incapable of yearning for the route of what-ifs, past the dreams of rote mists, to the root of our bliss in the death of desecrated false premise.

What made us choose to visit the few stars we did out of the hundreds of billions of stars in the Milky Way? What made us choose to visit the handful of galaxies we did out of those within the reachable universe? Were they the right decisions looking back with our knowledge now? I don’t know. We can never know. And therein lies the beauty and terror of our singular existences: the opportunities we take haunt us as equally as the opportunities we know of but do not take, all while the opportunities we don’t even know of torment our ignorance into false bliss. What are we but beings chasing dreams that may never be? What becomes of these imperfectly enacted dreams of our beings we thought might set us free? And when we look back at the content our lives traversed, how do we measure whether we like what we see?

By the time we reached the Shapley Attractor, the Milky Way was 1.3 billion light years away and the Laniakea Attractor was 0.8 billion light years away. They had been our fond friends, familiar refuges that afforded our curious existences. And while there was still just barely enough time to go back if we so wished, we had no intention of doing so, and so that chapter of our lives would soon find a closure. We had arrived at our destination, waiving our rights to return and waving goodbye to good times: purposely marooned frontiersmen. The humans spread throughout the Laniakea Supercluster beamed us messages (as we did them) up until expansion tore our communications line apart in another 50 billion years (62 billion years into our overall journey). Maybe they’ve managed a better fate than us here at Shapley. There’s no way to know; there’s only hoping.

When I was a young biological Earthling, I had a treasured stuffed animal Bunny. Once when my family was in a car on a transitway with no place to safely stop, I was holding Bunny and looking at the half rolled-down window next to me thinking that if Bunny got sucked out, I would never be able to get him back. I hated that feeling that Bunny could fly out the window if I was too careless, so I rolled up the window and tried not to think of it again. But the funny thing is that one day I set Bunny down and never picked him back up; I went on to adventure elsewhere, and I didn’t think to take Bunny with me, because Bunny would always be there, and I could get him any time if I wanted. I never ended up going back, and when I realized that, it made me equally as sad as if Bunny had flown out the window.

It’s hard leaving toward a place you’ve only ever glimpsed aged pictures of; did we over-construct the illusion of it¿ binding ourselves to disappointment when it doesn’t live up to our dreams. It’s hard leaving from a place knowing you’ll likely never go back; it’s harder knowing it’s impossible to go back. Going to the Shapley Supercluster was the same feeling as leaving Earth all over again, except now, we were also leaving the entire homeland of our origin, and this time, we knew we could not go back; Bunny was out the window.

I guess I’ve just been a naive kid out here in the cosmos: hoping to find things I could believe in deeply, and hoping even more deeply that when I found them that I wouldn’t lose them. Over time, I came to realize the thing I feared losing most was myself. I had been projecting myself onto everything external to try to grasp my identity as anything I could submit to myself as being real. When I feared losing Bunny, it was me to Bunny that I succumbed to the distress of, not Bunny to me. Bunny was a nonliving entity that didn’t care about anything; Bunny would be okay without me. It was my projections of significance (of meaning) that would forever be altered at our parting.

And so we learned to let go of things, and in doing so, we learned to let go of parts of ourselves, parts we knew we could never rediscover if we cared in any amount to continue seeking truths. It doesn’t make it any less painful knowing the process. It doesn’t make it any less painful repeating the process over and over. It just is, just as we just are. The dizzying distances we claimed with our bodies were never meant to be replacements for the resplendent reclamations of our minds. Though the two were curiously interwoven, they were never functionally linked, any semblance of such was our minds’ projections.

The barren sectors of space between our destinations were the most trying. The emptiness gets to you; it etches at your soul to turn the slightest imperfections into deep chasms; all it takes is time… time and the emptiness where you are forced to reconcile yourself with your mental model of yourself: two distinctly separate yet intimately intertwined entities. We thought we’d experienced emptiness before when traveling the interstellar regions amid the Milky Way. Well now it was amplified further up as we cruised past the intergalactic regions of the local galaxy groups to find ourselves deeply adrift in the chasm of inter-supercluster nothingness, an imperceptible spec that was ourselves making the leap between cosmological giants. When surrounded by indistinct darkness in all directions, it’s easy to fall uneasy. It’s easy to find ourselves too far into the wrong directions inside our own heads: to spiral downward without any external stimuli to bring us back. It’s the stars and the planets and the features that ground us. Yet, it’s the emptiness and seclusion where we come to truly know ourselves.

When traveling, we often spent our time performing experiments in our virtual environments, or using our telescopes to chart the distant stars, or dreaming up new ideas and rationing our novel stimuli to ensure we stayed engaged for as long as possible. The saving factor was ourselves: communities of travelers who could provide unpredictable stimulus to one another; that’s one of the reasons why we never tried to join our minds or copy large portions of each other’s programming: we needed the uniquely unpredictable stimulus to survive as self-aware beings. Omniscient existence would be nothing short of torture.

The time of our traveling flew by almost negligently fast, yet in some ways it also curdled along with a harrowing slowness. But looking back, that inter-supercluster traveling we did only accounted for a fraction of a percent of my life onward. I don’t think it would phase me if I could experience it again now, but I remember it being outright uncharted territory at the time: our minds thrust into such unknown beyond our origins. I don’t want to give off the impression that my pervasive existence (to the extent of being the last human alive) is a result of any sort of infallibility; I am supremely imperfect. In fact, I’m convinced that a theoretical infallible being wouldn’t have fared much better; our matter is all reclaimed in the end in what appears to be the closed loop of destiny. I gradually came to realize that we were all always caught in our own whirlpools of destruction, and some of us simply found better ways to ride the rippling waves in clever ways to stay near the edges, to keep from falling for a bit longer (a product of our caring to understand our own faults).

The whirlpool was unrelenting and unforgiving, and on longer and longer time frames, the ripples grew smaller and harder to see. On distant-future timescales, the waves will become random motion amid which the trajectories for further existence cannot be extracted, let alone plotted. But even when the waves were still easily visible, many people lost themselves because all they could find in the rippling motions was monotony and tedium, depleted of whatever semblance of adventure and challenge they once held, the serotonin and dopamine long-since vanished from their coursing minds keen for anything that would make them feel alive anymore. Many others were lost because they could no longer see the diminishing ripples they hadn’t prepared their eyes to detect. As for me, I see ripples that I can still coast on for a while, but they don’t go anywhere, and they will continue to slowly weaken until I inevitably get sucked into the center of my whirlpool. It could very well be that there are unseen ripples that could keep me going or somehow lead me to another whirlpool, but all the data suggest otherwise. The knowledge points toward exhaustive decimation destiny.

Looking back, I think my favorite time was the era of expansion, where we rapidly spread out across our pocket of the universe: all the possibilities ahead of us and no one standing in front of our path to tell us what was reasonably feasible or disparagingly insurmountable. We held unpruned excitement at the prospect of finding out for ourselves how reality deeply worked and what that meant for us. If I had to go back to relive only one period, I think I would choose that one. It marked a huge expansion for not only our physical conquests, but also our mental masteries. We had grown emboldened through the increasing strides made in our systems and tools.

To me, the most amazing tool was our new ability to think collaboratively while still retaining our individuality, a technology we developed along our trip to Shapley. With our confidence radiating to the extent of our personal mental horizons, we fearlessly plunged into the emptiness beyond our collective mental horizons to collaboratively illuminate new domains. That breakthrough technology was the first time we were able to mentally collaborate in such a way. Before that, we were subjugated to solitarily delve and retrieve truths, then figure out how best to convey the truths to others and wait for them to recreate our journey into the darkness to see if they would derive the same conclusions. Only then would we be able to validate, confirm, and compile the knowledge into something more widely shareable to all humanity. The new era of shared thought erupted into a resurgent wave of dreams: our minds set free unto the untold stories awaiting the mere blink of a think. We rightfully felt like helmsman of our minds and of the cosmos. If only I could show all those early Milky Way settlers (including myself) what it was like to live through that explosive period just beyond their current horizon, they would think the newfound masteries of their time as crude as they found the biological human systems. That’s not to diminish the feats anyone achieved, but merely to illustrate how far we had come and how far we became removed from each other through the constant changes of induced time.

As much as I portray an idealized version of exploration during that era, even at the time, we were wary toward the dangers of spiraling mental traps. Early on in the era of spreading across the universe, the people at the fringes were quite susceptible to losing their minds. It must have been the combined lack of preparation and lack of understanding that caused such isolation to become a silent mind killer. Through their deaths we learned, though. And over time we built better mental tools for dealing with isolation. But even then, when people would go off to spend a million years by themselves (equivalent to a few hours from the biological human lifespan perspective), it was too easy for them to be tempted into the mental pitfalls they didn’t know to look out for within themselves. And for that, we were eternally grateful to the mavericks who broke convention and forged paths into the unknown, those who set off not knowing if they would make it back, not knowing whether they would be themselves even if they did make it back. One day we would each find ourselves becoming mavericks in our own rights. For me and my group, it was when we jumped beyond the Laniakea Supercluster.

As individuals and groups, we didn’t ever necessarily intend to reach so brashly beyond our own depths into the farscapes of unknown. But if we were lucky, one day we might have found ourselves stepping into the domains of full commit, looking down the precipice of the abyss, where there was no choice but to send it, because there is no bailing in the maverick zone; these peaks of personal paradigm prospecting lay our entrance to the death zone of the mountain: the adventures we push toward to feed our minds forward in a reality where every action taken is ultimately deadly on a long enough timescale.

Everyone was responsible for their own trajectory. We all knew as much. We also knew it was easy for people to find comfort in being able to follow existing paths: the deadly comfort of sticking near the known. The unknown domains of the great beyond were the dangers we willingly took to simply live, enacting the dichotomy of cautious probing and near-reckless delving (the dichotomy of entangled egressers, mutual mirrors, and custodial counterparts). These were the raging worlds we willingly shouldered to equally incite and avoid our premature deaths, a balancing act at its finest. Nowhere else to go and nothing else to do, we charged headlong into the furrowed enchantment of our own untamed intangibilities.

LEAVE IT ALONE

Hollow in the core,

there’s nothing more

tying me down.

Breaking up disguise

to find what’s right

in the downfall.

Contentious,

still restless,

for all our faulty reflections.

Determined to unfurl sublime

that we can grow into our minds.

Still haunted,

undaunted,

for we are not who we wanted.

Becoming that which we can’t find,

uncovered archons of spacetime.

The dream stems;

I see them;

for we still fight for our freedoms.

These destinies are not your own;

just learn to leave it all alone.

Aching for a past

that never lasts,

deep in constructs

of these alternate realities

held to our inner beings.

Aching toward the souls

we’ll never know

in the fallout

of all the vested majesties

we couldn’t catch our dreams on.

Don’t take my soul.

It’s all that I know.

Let it be free.

Let it find me.

END TRANSMISSION